Dr Jamil Darrouj

- Pulmonary/Critical Care Division

- Cooper University Hospital

- Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

- 393 Dorrance

- Camden

- USA

Several major sleep disorders are highlighted by their differences from the normative pattern pregnancy trimester breakdown purchase ginette-35 uk. Sleep Definitions According to a simple behavioral definition pregnancy urine test order ginette-35 2 mg on-line, sleep is a reversible behavioral state of perceptual disengagement from and unresponsiveness to the environment women's health volunteer opportunities buy ginette-35 2mg mastercard. It is also true that sleep is a complex amalgam of physiologic and behavioral processes menstrual like cramping in third trimester ginette-35 2 mg amex. Sleep is typically (but not necessarily) accompanied by postural recumbence, behavioral quiescence, closed eyes, and all the other indicators one commonly associates with sleeping. These behaviors can include sleepwalking, sleeptalking, teeth grinding, and other physical activities. Anomalies involving sleep processes also include intrusions of sleep—sleep itself, dream imagery, or muscle weakness—into wakefulness, for example (Box 2-1). This manual recommends alterations to recording methodology and terminology that the Academy will demand of clinical laboratories in the future. Although specification of arousal, cardiac, movement, and respiratory rules appear to be value added to the assessment of sleep-related events, the new rules, terminology, and technical specifications for recording and scoring sleep are not without controversy. The current chapter uses the traditional terminology and definitions, upon which most descriptive and [17] experimental research has been based since the 1960s. Although these are somewhat trivial changes, changes in nomenclature can result in confusion when attempting to compare to previous literature and established data sets and are of concern for clinicians and investigators who communicate with other fields. The rationale for the change is that the frontal placements pick up more slow-wave activity during sleep. Within sleep, two separate states have been defined on the basis of a constellation of physiologic parameters. The four electroencephalogram tracings depicted here are from a 19-year-old female volunteer. Each tracing was recorded from a referential lead (C3/A2) recorded on a Grass Instruments Co. On the second tracing, the arrow indicates a K-complex and the underlining shows two sleep spindles. The distinction of tonic versus phasic is based on short-lived events such as eye movements that tend to occur in clusters separated by episodes of relative quiescence. This fundamental principle of normal human sleep reflects a highly reliable finding and is important in considering normal versus pathologic sleep. Definition of Sleep Onset the precise definition of the onset of sleep has been a topic of debate, primarily because there is no single measure that is 100% clear-cut 100% of the time. To begin a consideration of this issue, let us examine the three basic polysomnographic measures of sleep and how they change with sleep onset. A further complication is that sleep onset often does not occur all at once; instead, there may be a wavering of vigilance before “unequivocal” sleep ensues (Fig. Note that the electroencephalographic pattern changes from wake (rhythmic alpha) to stage 1 (relatively low-voltage, mixed-frequency) sleep twice during this attempt to fall asleep. Different functions, such as sensory awareness, memory, self-consciousness, continuity of logical thought, latency of response to a stimulus, and alterations in the pattern of brain potentials all go in parallel in a general way, but there are exceptions to every rule. One might not always be able to pinpoint this transition to the millisecond, but it is usually possible to determine the change reliably within several seconds. The following material reviews a few common behavioral concomitants of sleep onset. Keep in mind that “different functions may be depressed in different sequence and to [3] different degrees in different subjects and on different occasions” (p. Simple Behavioral Task In the first example, volunteers were asked to tap two switches alternately at a steady pace. This is an example of what one may think of as the simplest kind of “automatic” behavior pattern. Because such simple behavior can persist past sleep onset and as one passes in and out of sleep, it might explain how impaired, drowsy drivers are able to continue down the highway. When volunteers are queried afterward, they report that they did not see the light flash, not that they saw the flash but the response was inhibited. This is one example of the perceptual disengagement from the environment that accompanies sleep onset. Auditory Response In another sensory domain, the response to sleep onset is examined with a series of tones played over earphones to a subject who is instructed to respond each time a tone is heard. Olfactory Response When sleeping humans are tasked to respond when they smell something, the response depends in part on sleep state and in part on the particular odorant. In contrast to visual responses, one study showed that responses to graded strengths of peppermint (strong trigeminal stimulant usually perceived as pleasant) and pyridine (strong trigeminal stimulant usually perceived as extremely unpleasant) were well [7] maintained during initial stage 1 sleep. On the other hand, a tone successfully aroused the young adult participants in every stage. One conclusion of this report was that the olfactory system of humans is not a good sentinel system during sleep. Response to Meaningful Stimuli One should not infer from the preceding studies that the mind becomes an impenetrable barrier to sensory input at the onset of sleep. Indeed, one of the earliest modern studies of arousability during sleep [8] showed that sleeping human beings were differentially responsive to auditory stimuli of graded intensity. Another way of illustrating sensory sensitivity is shown in experiments that have assessed discriminant responses during sleep to meaningful versus nonmeaningful stimuli, with meaning supplied in a number of ways and response usually measured as evoked K-complexes or arousal. From these examples and others, it seems clear that sensory processing at some level does continue after the onset of sleep. Another fairly common sleep-onset experience is hypnic myoclonia, which is experienced as a general or localized muscle contraction very often associated with rather vivid visual imagery. Hypnic myoclonias are not pathologic events, although they tend to occur more commonly in association with stress or with unusual or irregular sleep schedules. A response by the individual to the image, therefore, results in a movement or jerk. One view is that it is as if sleep closes the gate between short-term and long-term [13] memory stores. During a presleep testing session, word pairs were presented to volunteers over a loudspeaker at 1-minute intervals. As illustrated in Figure 2-6, the 30 second condition was associated with a consistent level of recall from the entire 10 minutes before sleep onset. Figure 2-6 Memory is impaired by sleep, as shown by the study results illustrated in this graph. In the 30-second condition, therefore, both longer-term (4 to 10 minutes) and shorter-term (0 to 3 minutes) memory stores remained accessible. In the 10-minute condition, by contrast, words that were in longer-term stores (4 to 10 minutes) before sleep onset were accessible, whereas words that were still in shorter-term stores (0 to 3 minutes) at sleep onset were no longer accessible; that is, they had not been consolidated into longer-term memory stores. One conclusion of this experiment is that sleep inactivates the transfer of storage from short to long-term memory. Another interpretation is that encoding of the material before sleep onset is of insufficient strength to allow recall. The precise moment at which this deficit occurs is not known and may be a continuing process, perhaps reflecting anterograde amnesia. Nevertheless, one may infer that if sleep persists for approximately 10 minutes, memory is lost for the few minutes before sleep. Patients with syndromes of excessive sleepiness can experience similar memory problems in the daytime if sleep becomes intrusive. Learning and Sleep In contrast to this immediate sleep-related “forgetting,” the relevance for sleep to human learning— [14],[15] particularly for consolidation of perceptual and motor learning—is of growing interest. The [16] importance of this association has also generated some debate and skepticism. Progression of Sleep Across the Night Pattern of Sleep in a Normal Young Adult the simplest description of sleep begins with the ideal case, the normal young adult who is sleeping well and on a fixed schedule of about 8 hours per night (Fig. In general, no consistent male versus female distinctions have been found in the normal pattern of sleep in young adults. Figure 2-7 the progression of sleep stages across a single night in a normal young adult volunteer is illustrated in this sleep histogram. This histogram was drawn on the basis of a continuous overnight recording of electroencephalogram, electrooculogram, and electromyogram in a normal 19-year-old man. First Sleep Cycle the first cycle of sleep in the normal young adult begins with stage 1 sleep, which usually persists for only a few (1 to 7) minutes at the onset of sleep. In addition to its role in the initial wake-to-sleep transition, stage 1 sleep occurs as a transitional stage throughout the night.

The nurse is caring for a patient undergoing pulmonary artery does this information indicate to the nurse about the patient’s pressure monitoring menstrual cycle 7 days purchase ginette-35 2 mg otc. Administer the drug as ordered menstrual 5 days early ginette-35 2 mg otc, monitoring respiratory How should the nurse interpret these assessment findings? What would be an appropriate goal of nursing to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy ask how it is possible that care for this patient? State the importance of continuing intravenous antibiotic before he died menstrual 3 weeks cheap 2 mg ginette-35 visa, but he may not have thought them important therapy as ordered breast cancer breakthrough order 2mg ginette-35. During exercise, the heart may not be able to meet expect to auscultate in this patient? A patient considering heart valve replacement asks if a biologic and can lead to changes in the heart’s rhythm or the out or mechanical valve is better to use. How should the nurse re flow of blood from the heart in people with hypertrophic spond to the patient? Biologic valves tend to be more durable than mechanical See Test Yourself answers in Appendix B. The need to take drugs to prevent rejection of biologic tissue is a major consideration. Clotting is a risk with mechanical valves, necessitating anticoagulant drug therapy after insertion. Endocarditis is a risk following valve replacement that is more easily treated with mechanical valves. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice failure fact sheet. The right of Sam Kaddoura to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier website at. As new research and experience broaden our knowledge, changes in practice, treatment and drug therapy may become necessary or appropriate. Readers are advised to check the most current information provided (i) on procedures featured or (ii) by the manufacturer of each product to be administered, to verify the recommended dose or formula, the method and duration of administration, and contraindications. It is the responsibility of the practitioner, relying on their own experience and knowledge of the patient, to make diagnoses, to determine dosages and the best treatment for each individual patient, and to take all appropriate safety precautions. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the Author assumes any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property arising out or related to any use of the material contained in this book. It is a powerful and safe technique which has become widely available for cardiovascular investigation. The training of medical students and newly qualified doctors often includes an introduction to echo. While there are many detailed texts of echo available, aimed primarily at cardiologists and those performing echo examinations, such as cardiac technicians, there are few simply introductory texts. This book aims to provide a practical and clinically useful introduction to echo – much of which is easy – for those who will be using, requesting and possibly interpreting it in the future. It is also hoped that it may be of interest to other groups – established physicians, surgeons and general practitioners, cardiac technicians, nurses and paramedics. It aims to explain the echo techniques available, what an echo can and can’t give, and – importantly – puts echo into a clinical perspective. It is by no means intended as a complete textbook of echo and some aspects are far beyond its scope. This new edition has become necessary because of advances in echocardiography over the past six years. The section on diastolic function has been expanded with the addition of tissue Doppler imaging, and the section on pericardial disease has been made more detailed. There are expanded sections on newer echo techniques such as 3-D echo, stress echo and contrast echo and a new section on pulmonary embolism. Special clinical situations now include echo changes with advanced age, the athletic heart, obesity and diet drugs. I also should like to thank Dr Phil Carrillo, Dr Gerry Carr-White, Dr Michael Henein, Dr Rohan Jagathesan, Mrs Johan Carberry, Mrs Myrtle Crathern, Mrs Renomee Porten, Mrs Sonia Williams, Dr Sanjay Prasad, Mrs Denise Udo and Dr Ihab Ramzy. I am also very grateful to Miss Natalie McDonnell, Dr Jamil Mayet, Dr Rakesh Sharma, Dr Wei Li, Miss Beth Unsworth and Mr Graham Clark. Last but not least, many thanks to Mrs Janice Urquhart, Ms Christine Johnston and Mr Laurence Hunter of Elsevier for their support and patience! Echo is easy to understand as many features are based upon simple physical and physiological facts. It is a practical procedure requiring skill and is very operator dependent – the quality of the echo study and the information derived from it are influenced by who carries out the examination! This chapter deals with: ● Ultrasound production and detection ● the echo techniques in common clinical use ● the normal echo ● Who should have an echo. Ultrasound production and detection Sound is a disturbance propagating in a material – air, water, body tissue or a solid substance. Sound of frequency higher than 20 kHz cannot be perceived by the human ear and is called ultrasound. As a rough estimate, the smallest size that can be resolved by a sound is equal to its wavelength. On the other hand, the smaller the wavelength of the sound, the less its penetration 1 66485457-66485438 A higher frequency of ultrasound can be used in children since less depth of penetration is needed. Ultrasound results from the property of certain crystals to transform electrical oscillations (varying voltages) into mechanical oscillations (sound). The same crystals can also act as ultrasound receivers since they can effect the transformation in the opposite direction (mechanical to electrical). When varying voltages are applied to the crystal, it vibrates and transmits ultrasound. When the crystal is in receiving mode, if it is struck by ultrasound waves, it is distorted. This fixes the function of the crystal – it emits a pulse and then listens for a reflection. When ultrasound propagates in a uniform medium, it maintains its initial direction and is progressively absorbed or scattered. If it meets a discontinuity such as the interface of 2 parts of the medium having different densities, some of the ultrasound is reflected back. Ultrasound meets many tissue interfaces and echo reflections occur from different depths. The time delay between transmission of the pulse and reception of the reflected echo 2. The intensity of the reflected signal, indicating the echo-reflectivity of that tissue or tissue–tissue interface. The signals that return to the transducer therefore give evidence of depth and intensity of reflection. The transducer usually has a line or dot to help rotate it into the correct position to give different echo views. The subject usually lies in the left lateral position and ultrasound jelly is placed on the transducer to ensure good images. A number of sections of the heart are examined by echo from these transducer positions, which are used for 2 main reasons: 1. There is a limitation determined by the anatomy of the heart and its surrounding structures 2. Useful echo information can be obtained in most subjects, but the study can be technically difficult in: 3 66485457-66485438

Effective ginette-35 2mg. First Week Pregnancy Symptoms in Hindi | गर्भवती होने के लक्षण.

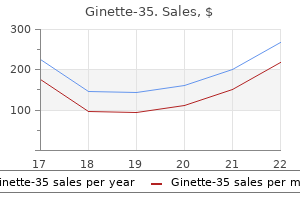

Overall patient satisfaction was high womens health wise purchase 2mg ginette-35 with mastercard, but significantly more patients rated satisfaction as high/very high in the standard management versus telemedicine group (96% versus 74%; p=0 pregnancy 8 weeks symptoms generic 2 mg ginette-35 overnight delivery. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Open Funder Registry breast cancer xmas tree discount ginette-35 online visa. It is characterised by recurrent collapse of the upper airway during sleep women's health clinic dunedin buy discount ginette-35 2 mg on-line, leading to nocturnal hypoxaemia, sleep fragmentation and daytime hypersomnolence. Given the high motivation of both professionals and patients to be involved, no dropouts were anticipated and thus a total of 100 patients were planned to be recruited. The study was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee and registered at ClinicalTrials. This included a practical demonstration of how to put on the mask, and the correct management and cleaning of the tubes, masks and humidifier. All patients were visited after 1 month of treatment by the specialist nurse at the sleep unit. Costs Total direct and indirect costs of each intervention were assessed to perform cost and cost-effective analyses. The costs of hospital visits and telephone consultations with sleep unit physicians were assessed using prices provided by the Catalan Institute of Health [20]. Statistical analysis Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, while categorical variables were reported as absolute numbers and percentages. Differences between study groups were assessed using the Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test to compare dichotomous variables, and the t-test for continuous variables. Linear or logistic regression analyses were used, as appropriate, to compare differences between study groups. Cost differences between study groups were assessed using the Mann–Whitney two-sample statistic. All analyses were performed on both an intention-to-treat and a per-protocol basis. Results A total of 100 subjects were randomised: 48 to standard care and 52 to telemedicine. Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics in the two intervention groups are shown in table 1. The only significant differences between the standard and telemedicine groups at baseline were a lower waist/hip ratio and a higher incidence of dyslipidaemia in the telemedicine versus standard care group (table 1). All results presented are for the intention-to-treat analysis; similar results were obtained in the per-protocol analysis. Patients managed using telemedicine reported significantly lower overall satisfaction than those receiving standard care and tended to be less satisfied about appropriate contact with the hospital (table 3). Overall, patients managed using telemedicine placed a positive value on all aspects of the telemonitoring programme, with the exception of privacy aspects (table 3). Values for direct and indirect costs assessed during the study are summarised in table 4. The total average cost per randomised patient was 28% lower in the telemonitoring group than in the standard care group. This was primarily a result of lower costs for planned follow-up visits to the sleep unit, which are not required when telemonitoring is used. This is in contrast to the results of a Canadian randomised controlled trial enrolling 75 patients that showed a better compliance with auto-titrating positive airway pressure after 3 months of −1 management using telemonitoring compared with standard care (191±147 versus 105±118 min·day ; p=0. These contrasting results could be explained by differences between the studies in terms of compliance in control patients. However, the results of these trials were inconsistent, thus reinforcing the idea of the additional efficacy of telemonitoring strategies being highly dependent on the baseline characteristics and compliance of the target population, as well as the proposed telemedicine intervention. A key aspect of any new treatment strategy, including telemedicine, is the cost of the intervention and its cost-effectiveness. The main source of savings in the telemedicine arm was the reduction in planned monitoring visits, which were partially replaced by a remote intervention. The combination of lower management costs and similar compliance compared with standard care meant that the intervention was cost-effective. We expected that a reduction in the number of clinic/hospital visits combined with easy monitoring would be appreciated by patients. However, although patient satisfaction was high in both groups, it was significantly higher in the standard management group. First, patients willing to participate in a clinical trial are usually highly motivated and thus may be less concerned about avoiding hospital visits than an average patient. Finally, as reported in the specific telemonitoring questionnaire, some patients reported concerns about their privacy, either because they were contacted due to low compliance or because their compliance data were held by non-hospital-based medical personnel. However, most patients placed a positive value on the usefulness of online information and telemonitoring. Therefore, there is obviously room for improvement regarding patient satisfaction with the telemedicine strategy used in this study. We hypothesise that there may be an initial barrier preventing patients from fully embracing and feeling comfortable with telemonitoring. Savings generated by use of the telemedicine approach, via avoidance of planned visits to the sleep unit, were significant and had an important impact in terms of cost-effectiveness. Moreover, telemonitoring could facilitate a reduction of the care burden at sleep units that are already operating at, or close to , maximum capacity. First, the assessment of patient satisfaction was performed using a nonvalidated questionnaire. The high level of compliance in the standard management group could have masked any potential benefits of telemonitoring. The exclusion of patients with other associated sleep disorders (periodic limb movements or other parasomnias), severe comorbidities. Such patients are likely to be the ideal population for telemonitoring programmes. However, patients with more complex presentations are likely to benefit the most from standard management including close follow-up in sleep units. All cost analyses are highly dependent on the characteristics of the healthcare setting in which they are conducted. Therefore, extrapolation of the results to different settings should be done cautiously. Moreover, the possibility of unrealistic pricing of the supplied telemonitoring services cannot be completely ruled out, although sensitivity analyses increasing such costs by 25% and 50% were performed. Finally, the short follow-up period of this study (3 months) does not allow the extrapolation of the results to the long term. Moreover, telemonitoring was associated with lower patient satisfaction compared with standard care. An extended follow-up period is needed to evaluate the long-term reproducibility of these results. All authors were involved in the revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. Association between treated and untreated obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hypertension. Obstructive sleep apnea and systemic hypertension: longitudinal study in the general population. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Long-term effect of continuous positive airway pressure in hypertensive patients with sleep apnea. Continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for systemic hypertension in people with obstructive sleep apnoea: randomised controlled trial. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on the incidence of hypertension and cardiovascular events in nonsleepy patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Long-term adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy in non-sleepy sleep apnea patients. Long-term acceptance of continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea. The impact of a telemedicine monitoring system on positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. A Bayesian cost-effectiveness analysis of a telemedicine-based strategy for the management of sleep apnoea: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. A telemedicine intervention to improve adherence to continuous positive airway pressure: a randomised controlled trial.

Bifulco M pregnancy cravings purchase ginette-35 cheap online, Laezza C breast cancer lumpectomy purchase ginette-35 visa, Portella G pregnancy costumes purchase ginette-35 2mg visa, Vitale M womens health 40 years old ginette-35 2 mg free shipping, Orlando P, De Petrocellis L, DiMarzo V. Control by the endogenous cannabinoid system of ras oncogene-dependent tumor growth. Anti tumoral action of cannabinoids: involvement of sustained ceramide accumulation and extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Transcriptional regulation of the cannabinoid receptor type 1 gene in T cells by cannabinoids. Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors. High level of cannabinoid receptor 1, absence of regulator of G protein signaling 13 and differential expression of Cyclin D1 in mantle cell lymphoma. Cannabinoid receptor-independent cytotoxic effects of cannabinoids in human colorectal carcinoma cells: synergism with 5 fluorouracil. Inhibition of cancer cell invasion by cannabinoids via increased expression of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1. Increased expressions of cannabinoid receptor-1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 in human prostate carcinoma. Anandamide induces apoptosis in human cells via vanilloid receptors: evidence for a protective role of cannabinoid receptors. Arachidonyl ethanolamide induces apoptosis of uterine cervix cancer cells via aberrantly expressed vanilloid receptor-1. Opposing actions of endocannabinoids on cholangiocarcinoma growth: recruitment of Fas and Fas ligand to lipid rafts. The endogenous cannabinoid, anandamide, induces cell death in colorectal carcinoma cells: a possible role for cyclooxygenase 2. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression is involved in R(+)-methanandamide-induced apoptotic death of human neuroglioma cells. Antitumor effects of cannabidiol, a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid, on human glioma cell lines. Cannabidiol inhibits human glioma cell migration through a cannabinoid receptor-independent mechanism. Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. A cannabinoid quinone inhibits angiogenesis by targeting vascular endothelial cells. Anandamide inhibits Cdk2 and activates Chk1 leading to cell cycle arrest in human breast cancer cells. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits cell cycle progression in human breast cancer cells through Cdc2 regulation. Delta 9 tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits cell cycle progression by downregulation of E2F1 in human glioblastoma multiforme cells. Inhibition of apoptosis by survivin predicts shorter survival rates in colorectal cancer. Cannabinoid receptor activation induces apoptosis through tumor necrosis factor alpha-mediated ceramide de novo synthesis in colon cancer cells. Cannabinoids induce apoptosis of pancreatic tumor cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes. Involvement of sphingomyelin hydrolysis and the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in the Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced Cancer Metastasis Rev. Hermanson and Marnett Page 17 stimulation of glucose metabolism in primary astrocytes. Cannabinoid receptor mediated apoptosis induced by R(+)-methanandamide and Win55, 212-2 is associated with ceramide accumulation and p38 activation in mantle cell lymphoma. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol induced apoptosis in Jurkat leukemia T cells is regulated by translocation of Bad to mitochondria. Cannabinoid receptor agonists are mitochondrial inhibitors: a unified hypothesis of how cannabinoids modulate mitochondrial function and induce cell death. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of anandamide in human prostatic cancer cell lines: implication of epidermal growth factor receptor down-regulation and ceramide production. Suppression of nerve growth factor Trk receptor and prolactin receptors by endocannabinoids leads to inhibition of human breast and prostate cancer cell proliferation. Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits epithelial growth factor induced lung cancer cell migration in vitro as well as its growth and metastasis in vivo. Antiangiogenic activity of the endocannabinoid anandamide: correlation to its tumor-suppressor efficacy. Molecular and genetic profiling of prostate cancer: implications for future therapy. Growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vivo requires specific cleavage of fibrillar type I collagen. Blázquez C, Salazar M, Carracedo A, Lorente M, Egia A, González-Feria L, Haro A, Velasco G, Guzmán M. Cannabinoids inhibit glioma cell invasion by down-regulating matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression. Blázquez C, Carracedo A, Salazar M, Lorente M, Egia A, González-Feria L, Haro A, Velasco G, Guzmán M. Down-regulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 in gliomas: a new marker of cannabinoid antitumoral activity? Differential requirement of protein tyrosine kinases and protein kinase C in the regulation of T cell locomotion in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Anandamide is an endogenous inhibitor for the migration of tumor cells and T lymphocytes. Matrix metalloproteinases: molecular aspects of their roles in tumour invasion and metastasis. Intestinal trefoil factor promotes invasion in non-tumorigenic Rat-2 fibroblast cell. Upregulation of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 confers the anti-invasive action of cisplatin on human cancer cells. Cannabinoids reduce ErbB2-driven breast cancer progression through Akt inhibition. Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit tumor growth and metastasis of breast cancer. Pathways mediating the effects of cannabidiol on the reduction of breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol enhances breast cancer growth and metastasis by suppression of the antitumor immune response. E have been recovered in northern China, and the plant’s use as a medicinal and mood altering agent date back nearly as far. In 2008, archeologists in Central Asia discovered over two pounds of cannabis in the 2,700-year-old grave of an ancient shaman. After scientists conducted extensive testing on the material’s potency, they affirmed, “[T]he most probable conclusion. In the United States, federal prohibitions outlawing cannabis’ recreational, industrial, and therapeutic use were first imposed by Congress under the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 and then later reaffirmed by federal lawmakers’ decision to classify the cannabis plant - as well as all of its organic chemical compounds (known as cannabinoids) - as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. This classification, which categorizes the plant alongside heroin, defines cannabis and its dozens of distinct cannabinoids as possessing ‘a high potential for abuse. In July 2011, the Obama Administration rebuffed an eight-year old administrative inquiry seeking to reassess cannabis’ Schedule I status, opining: “[T]here are no adequate and well controlled studies proving (marijuana’s) efficacy; the drug is not accepted by qualified experts. At this time, the known risks of marijuana use have not been shown to be outweighed by specific benefits in well-controlled clinical trials that scientifically evaluate safety and efficacy. Following one week of evidentiary hearings, the judge ruled that the federal law ought to remain in place as long as there remains any dispute among experts as to cannabis’ safety and efficacy. The agency opined, “[T]here is no substantial evidence that marijuana should be removed from Schedule I. Despite the nearly century-long prohibition of the plant, cannabis is nonetheless one of the most investigated therapeutically active substances in history. While much of the renewed interest in cannabinoid therapeutics is a result of the discovery of the endocannabinoid regulatory system (which is described in detail later in this publication), much of this increased attention is also due to the growing body of testimonials from medical cannabis patients and their physicians, as well as from state-level changes to the plant’s legal status. The scientific conclusions of the majority of modern research directly conflicts with the federal government’s stance that cannabis is a highly dangerous substance worthy of absolute criminalization. The classification of marijuana as a Schedule I drug as well as the continuing controversy as to whether or not cannabis is of medical value are obstacles to medical progress in this area.